Greek born, London based contemporary dance choreographer Evangelia Kolyra creates complex, exciting and physically demanding work that challenges dancers.

Her first mid-scale work explores the impact of breath and breathing on the dancer’s body. With 10,000 litres of air circulating through the body every day, you can see how dancers’ bodies react, respond and reveal through their breathing.

Ahead of her show at Rich Mix on 12 May, we asked Evangelia about her meticulous choreography and 10,000 Litres:

What inspired you to start choreographing your own works?

The spark appeared during my studies in choreography. The excitement of playing, the curiosity of invention, the potential of the imagination and an inner urgency are what drove me and still drive me to make work.

How would you describe your own choreographic language, what defines your work?

Physically and mentally demanding for the performers, my work is detailed, complex in its simplicity, open to interpretation and contains a strong sense of dark humour.

It is mostly based on the choreography of functional actions which create a rich imagery and invite audiences to an experience which implies a plethora of suggested meanings and emotions.

It encourages them to be carried by their own imagination to a sphere where they can perceive information through a different lens.

Tell us about your new work 10,000 litres, which is your first mid-scale work…..

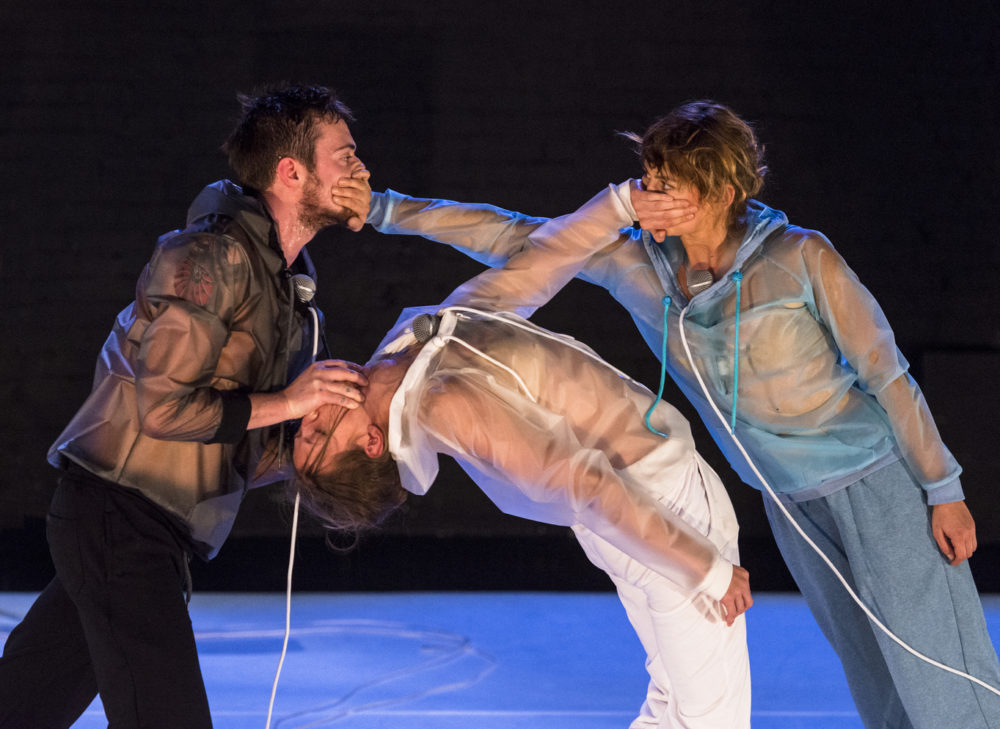

‘10,000 Litres’ cross-examines movement with the ways the human body is seen by science, in order to show its polysemy on stage and explore issues of co-existence, power and freedom.

Three performers focus on one of the most important bodily functions, the breath, exploring ways in which it affects movement and the body.

As a bodily function, breathing often exposes a dancer: the fatigue or the tension with which they move, their resignation, or the forced need to obey stage codes.

In this sense, it reveals the human dimension within the pure language of movement. The performers explore the functionality of their bodies and how this can translate into an exploration of an alternative reality whilst based on very realistic limitations.

The constant search for the senses attempted in this production, not only reveals the vital function of breathing but also brings out the issues of rhythm and vulnerability; the thin balance between its uninterrupted flow and its forced interruption.

This particular internal gaze and its political overtones regarding authority, freedom, and existence bring back the body at the epicentre of stage explorations.

The strong, immediate and visceral experience provided by the show affects directly the audience’s bodies. Audiences synchronise and identify with the performers’ breathing statements and become participants.

How did you come up with the concept?

Ideas come to me at unexpected moments and most of the times while working in the studio. I was working on another concept that never came to life and instead this idea of working with the movement of breath was revealed.

The concept of the whole work arrived much later. In the first stages and for quite a long period we worked on the idea trying out whatever emerged and gradually the concept fell into place.

I think the concept is already contained in the idea but it usually takes me a while to give it the right direction.

Your work is meticulous and physically demanding, tell us about the rigours required of dancers performing your work.

The work is demanding while being performed but also during the research and development period. While making ‘10,000 litres’, we faced both physical and mental challenges.

Experimenting with ways of alternating the natural breathing pattern and studying how this affects the body but also noticing how the breath is affected when challenging the normal body condition, required a huge amount of concentration and stamina.

Since breath is linked with our emotions, the research also triggered in us issues related to our personalities and psychological states.

This is something that is revealed as an idea during the performance but it was even more obvious and raw in the rehearsals. The strain I would say is less in the dancer’s body and more in the human body.

Do you feel that you have something specific to say that is different or new?

I don’t feel that I say something different or new. It is the approach and the way I decide to talk about things which matter to me that I hope are different or new.

The work is choreographed in a way that falls into the realm of the Theatre of the Absurd.

Audiences find a resemblance to Beckett’s work in the style, structure and the way the characters are developed and placed in a non-definable place but the basis of my work is movement.

The texts we created and the way they are delivered along with the movement create a humorous and visceral result.

The audience often feels a physical reaction in their own body while watching the performance.

You’ve got an MFA in Choreography from Roehampton University (UK), a BA in Dance from Greece and a BA in Greek Philology-Linguistics. How important has formal studies been do your dance and choreographic journey?

Very important. I learnt a lot through my studies. And somehow all I have learnt is already there in my work, many times without even trying.

I only realise when I see the work ready that the information that is there is from a learning experience of the past which is not limited to the formal studies of my adulthood but also from before or after that period.

And I had the luck to have some incredible teachers who have inspired and influenced the work I make and they keep on doing so without necessarily knowing.

Where do you get your inspirations?

I get inspiration from different projects and try to watch as much as possible. London is the perfect city for this.

My artistic practice is driven by my interest in the embodied nature of experience, the motional potential and function of the human body and its relation to socio-political and cultural factors.

I tend to allow the idea to emerge from the movement itself and then work with elements which refer to a universal realm. My interest is in finding unexpected stimuli and use ‘mistakes’ as inspiration.

In my work I employ a number of art forms to create performances in which the audience experiences a result that cannot be clearly identified as dance or theatre or performance art.

All these are complemented by my interest in the performative state of the performer during the creative process which influences and determines the creation of the work by offering rich material and information to be considered when making.

What advice would you give to other female choreographers?

Not sure if I am the right person to give advice as I am still trying to find my way around in the world of performance and art. I would say to anyone, the advice a friend gave me: If you feel you can do something else and be happy, then stop working as a choreographer. If not, then keep on going. Whoever insists, wins.

Get your tickets to 10,000 Litres at Rich Mix on 12 May here.