It is perhaps one of the great thrills of live performances that you know the people on stage are three-dimensional bodies moving in a three-dimensional space, subject to the same physical laws as you, and yet sometimes the stage makes them look flat, and escaping space-time all together. Ballet has always thrived on that thrill: classical dance, by defying the physics and gravitational pull of bodies, and modern dance by playing, with mesmerizing variety, on that defiance.

One such variety is the English 20th century tradition of modernity, which has often been associated with neo-classicism. Whilst its most quintessential representatives, the Royal Ballet’s Frederick Ashton (1904-1988) or Kenneth Macmillan (1929-1992) made romance central to the dance and therefore kept modern British dance essentially narrative, the outliers of that British tradition integrated (mostly American influences of) abstraction in a peculiar way. Yes to maintaining a connection to the other, a desire of the other at the heart of the choreography, but no to a reason why, no a happy, or sad, ending.

This much is supremely incarnated in the work of Richard Alston, a very British modernity in dance in which the outlier’s independent voice merges with tradition, sustained throughout a productive and successful career, and crowned this year, at age 70, by a knighthood for services to Her Majesty in dance. The Richard Alston Company has grown alongside the established ballet institutions since 1994 and is now dancing its last year. The Sadler’s Wells show was a penultimate compilation, celebrating a lifetime’s achievement with pieces selected from 2001 to 2018.

They highlight Alston’s brand of neoclassicism: a form and a vocabulary which has out-romanced dance, focusing on the graceful and flowing partnering between dancers, which is characteristic of his work, turning pas-de-deux’ into jewels of chivalrous dancing for the pure sake of harmony with no ulterior motive beside.

The first part of the evening is however a piece not by Alston, but by his long-term collaborator and the deputy director of the Company, Martin Lawrence. In addition to the merits of the piece in its own right, the work, entitled Detour, (first performed in September 2018 at Edinburgh), declares and confirms continuity: there is an heir and there is a legacy. So, though the company will disassemble next year, with Alston and Lawrence moonlighting for various companies around the world, the end is not the end of a certain idea of dance.

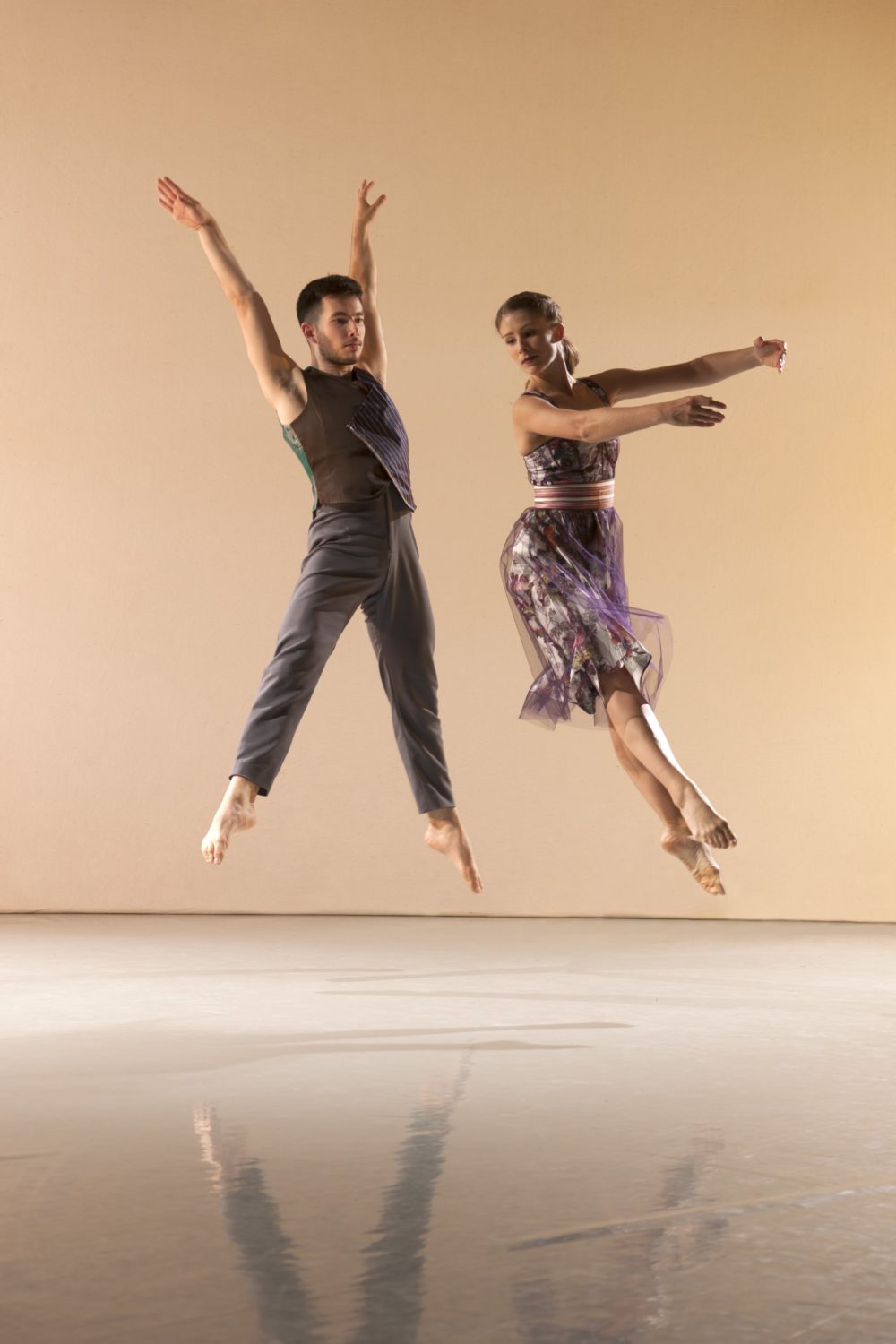

Lawrence’s piece is a case in point, a manifesto of Alstonianism: an inebriating flow of movement framed to the nano-detail with maniacal precision. The most striking element in the piece is the obsessive protectiveness of the male dancers over their female partners: each movement is anticipated with dazzling timing leaving no outstretched arm unseized, no desire to be lifted unfulfilled. In exchange, the girls shadow their men with an exactitude that glues the couples together. Continuous lines begin at the tip of the man’s head, and end with the toes of the lady.

This creates a depth of field, as the smaller female builds are doubled up, in perfect mirror-symmetry by the larger male outlines. Here is a ballroom dance partnering technique translated into the virtuosity of classical ballet grammar.

Lawrence creates perspective using limbs and arms to draw out the focal lines that manipulate the viewer into looking in a precise direction and paying attention to certain things. Our perception of the relation between the bodies on stage changes as the space between the dancers thickens. Each extension of arm and angling of legs is immediately duplicated in parallel lines by a mirror partner – the chivalrous man – creating a horizon line utterly controlled by the connections between the dancers. Movements are very quick all the better to create an effect of linearity and smoothness, persuading the audience that there is more room than there is.

The fluid watery material of the loose costumes accompanies the effect of a perfectly balanced closed sphere, very youthful, very airy, very out of reach of darkness and pain. When a darker hue invades the scene in the second half of the dance, as a new couple joins the first group, and the music is more menacing, subtle changes, like beige costumes instead of bright purple and solo moments, marking attempts at independence (soon foiled), contribute to thicken the space between the dancers.

The short pieces that follow, collectively entitled Quatermark, the highlights of a quarter of a century’s worth of choreography, are all by Alston from different moments in his career. They serve as the handbook for the particular grammar Alston has forged: that of precision, synchronicity and a play on light and heavy.

Three solos are followed by an ensemble piece showcasing his experimentation in framing the different shapes a dancer can create by pulling away from the floor. The intent is not to defy gravity, but rather to make the floor part of the dance.

And so, with Alston, there is a constant flirt with the possibility of heaviness. The pieces are pleasant and transition well to the most impressive work of the evening, Proverb, from 2006, set to typically haunting and electrifying music by Steve Reich.

The dancers move across the stage in mostly decelerating speed, as though the search is introverted now, digging for the secret of ordered movement rather than merely performing it.

The dancers wear costumes half coloured half black, everything is curvy in shades of auburn and desert red. The main theme is the transfer of weight from one side of the body to the other, from one dancer to the other. The chivalry is still there, but slowed down, its modalities unravelled. Very careful, measured stances underline the pendulum movements which bind couples and trios. The effect on the audience is that none of these movements are natural, no one would do this anywhere else, so we need to savour the moment that we come here to watch these dancers do these moves.

The last piece is less serious: a light-hearted virtuoso series of couples dancing to the well-known folk-inspired Hungarian dance variations by Brahms. The chivalrous boys are on cue, and the connections between the couples are a joy to watch.

There are moments in the duets which are screaming for point shoes, as the girls shuffle heavily across the stage with their merely human feet where point-shoes would have hovered briskly above ground, flying in a ‘bourrée-en-couru’. But then, of course, that is the point – not to make too fine a point of it: no points is the point. Where point-shoes incarnate the denial of the floor, the defiance of gravity, the modern neo-classical goes barefoot in the park and is proud of it.

Of course one wonders whether this all still is modern. Ballerinas began to take off their points before Alston was born. In its essence, modernity is always tomorrow and today is always too late, but the compromise of the present is in mixture and variety. It is those ingredients which help suspend time on stage and plunge the audience into the uncritical pleasures of the uniqueness of the moment.

Reviewed on 1st of March at Sadler’s Wells