The San Francisco Ballet is pulling all the stops on its London tour with not so much a programme as rather a dazzling cornucopia of everything they can do.

Of the four different shows the company is putting on this week, the first was an evening entirely choreographed by Alexei Ratmansky, currently the resident choreographer at American Ballet Theatre in New York, who built his reputation from freshening up classical ballets, from Romeo and Juliet to Sleeping Beauty, respecting the tradition and legacy of the great Russianised French master Marius Petipa, and building from ‘Petipa-tianism’, a classicism for our times.

He has the art of making the classical vocabulary of ballet still crisp, still communicative and – as demonstrated here at Sadler’s Wells – beyond delightful. This is no mean feat when the classical is assailed from every side by the contemporary dance-crusade against boundaries, against point shoes and against traditionally constructed duets. Ratmansky’s classical pas-de-deux are thrilling.

The show is entitled Shostakovich Trilogy, and is constituted of three distinct parts (created between 2012 and 2013), each set to a very different piece by the Russian composer whose life and career (born in 1906, died 1975) unfolded under the sinister maelstrom of the Soviet communist regime.

Each dance is given the title of the musical piece it is set to. No stories or plotlines. It is the music which leads the dance.

But what music! Beats and thumps from a hysteria-driven orchestra, screaming strings, moody introspective cellos, blaring trumpets, a romantic piano. No story is needed, we are plunged head-first into the beating heart: of elation, of passion, of regret and compelling merriment.

Shostakovich is a complex figure in himself, recently the subject of a novel by Julian Barnes, The Noise of Time: the post-communist Russians feel ambiguous towards him as both a high-profile establishment figure of his day, ultimately submissive to the regime (but what choice did he have?), as also a more complex subversive in the intricacies of his genius music. The West unanimously sees in him the translator into sound of what the terrible soviets did to the Russian Soul: violating it from its infinitely deep, yearnful and remorse-ravaged dark romanticism in the image of the anti-hero Eugene Onegin, into a ball of despair, hopelessness, crudeness and thick-skinned obtrusiveness like Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth from his censored opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District

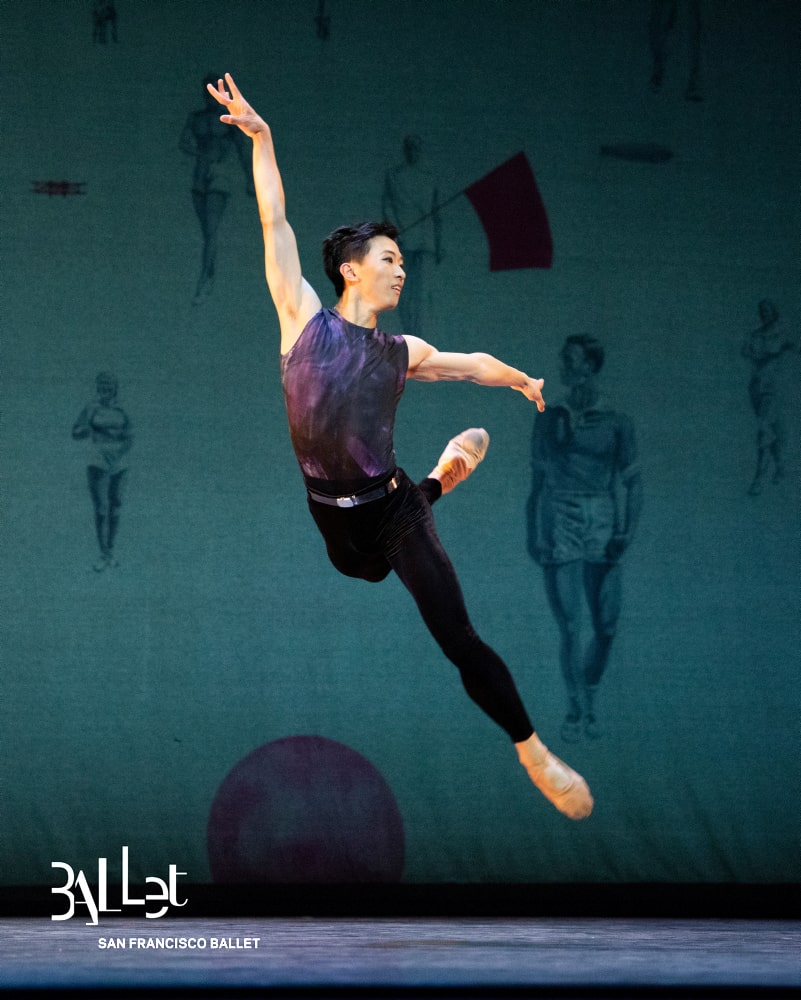

The music delivers a rawness of emotion which is the basic material from which the dance is forged. The first piece, Symphony n.9 is a sequence of alternating scenes of joy and bravado, tenderness and fatigue and cyclically renewed propulsions of energy. There is a perpetual motion which is shown to be purposefully contrived as the dancers move from high jumps to group formations, to humorously taunting a couple of lovers. The dancers emulate the innocence of land-workers whose energy derives directly from the earth-core. There is a lingering echo of Konstantin Levin on his farm, one of the soulful characters in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina who exalts in the tilling and ploughing of his land amongst the peasants, far away from the corruption of the city.

Ratmansky is a conqueror and explorer of space. He launches his dancers into all the invisible nooks and crannies of the stage like space-invaders. His favourite angle is oblique, which the dancers reach by first projecting their legs in straight lines and scouring, with delicate footwork, the space around the right angle to then claim the oblique as theirs to extend in – it is the uncharted space between the perpendicular and the straight.

There are enchanting innovative touches such as when a pair of couples walk away from the audience and lift their girls sideways, so that their legs jut out, like scissor blades, creating a depth of perspective through the layering of so many horizontal legs. A horizon of legs.

The second piece, Chamber Symphony, which is a work in which Shostakovich packed many self-quotations from other famous pieces of his, produces a dance focused on the madness and internal commotion of a male central dancer.

He is romantically dressed in black velvet trousers and jacket covering a bare pale chest. Again, it is hard to keep away from literary associations as the figure seems to be the incarnation of Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin, the hero of The Idiot. Three women appear soon enough as well, just like the three sisters Myshkin becomes entangled with in the novel.

The dancer is pursued by demons from within and from without, in the shape of an orderly group of male dancers who sway in perfect synchronicity to a harrowing dramatic unison of strings which feels like violent rain.

The music conjures groups of male and female dancers who evolve around the central figure like fate, harpies and temptations. Our hero extends his arms to them but he has not got the energy to really want to grasp them.

Hamlet-like in his indecision, his demons are Russian in flavour and gestures, with faint echoes of folk dancing in the high jumps of the men, landing with low bent knees. And the women tease him like no Ophelia would dare to.

He has a beautiful pas-de-deux with one of the three sisters, whom he then loses to melancholy or death, or indifference. It is once again, a particular lift which crystallises that lost communion with a sister-soul: the girl is held up high above the man’s head and the man does something extraordinary, he also lifts one long leg. With this dashing grand-battement at a perfect oblique angle to his partner high up in his arms, they create so many lines extended towards the sky.

The last piece is Piano Concerto n.1, a bravura piece in which trumpet and piano vie for attention: the first through sheer swagger, the second through mellifluous lyricism. It is a remarkable ensemble piece on stage, a parade of control and geometry verging on optical illusions.

The dancers, wearing bi-colour jumpsuits, appear shimmery-grey from the front and red hot from the back. Some of the men seem as though they are ready to explode out of the tightness of their costumes, reminiscent of the early revolutionary spirit of strength and muscle all at the service of the tender, small and fragile. In the 21st century, we more readily associate this with the camp. They are camp, but classy – or at least classical. There are humour and speed, precision and chorus-placement exactitude, which makes Ratmansky also an heir to George Balanchine, with a touch of devilish subversion and cheeky smiles.

The dancers, wearing bi-colour jumpsuits, appear shimmery-grey from the front and red hot from the back. Some of the men seem as though they are ready to explode out of the tightness of their costumes, reminiscent of the early revolutionary spirit of strength and muscle all at the service of the tender, small and fragile. In the 21st century, we more readily associate this with the camp. They are camp, but classy – or at least classical. There are humour and speed, precision and chorus-placement exactitude, which makes Ratmansky also an heir to George Balanchine, with a touch of devilish subversion and cheeky smiles.

Reviewed on 30th of May at Sadler’s Wells