Lest We Forget, a triple bill by English National Ballet returns to Sadler’s Wells to mark 100 years since the end of ‘the war to end all wars’.

It is apt that this sombre triptych of works by some of the UK’s leading choreographers – Liam Scarlett, Russell Maliphant and Akram Khan – has been returned 4 years after its premiere; it’s rerun reflecting that in war, there are no winners and that the emotional scars of intense battle do not disappear as soon as gunfire ends.

Liam Scarlett’s No Man’s Land starts the evening surprisingly, as the curtain raises on a phalanx of women, instead of a brigade of soldiers. Behind them, strewn along tiered steps are the bodies of uniformed men, highlighting the key theme of separation in Scarlett’s piece.

Slowly, the male dancers come back to life and re-join their female counterparts in romantic duets, the women clinging onto them in what seems to be a physical representation of the emotional weight that the soldiers are carrying on their shoulders. They are dancing together, yet even when touching, the pairs seem distant, as if they are dancing with the ghosts of their distant loved ones.

Throughout the piece the men and women separate and reconnect, showing how the war divided genders and created two opposing experiences. It would have been interesting if Scarlett delved further into the breadth of experiences within the genders themselves, as in its current form, the characters of No Man’s Land are anonymous, and function as representatives of a larger group rather than individuals.

Nevertheless, the choreography is aesthetically stunning and emotional, with one of the simplest, but most creative moments being when the female dancers retreat to work benches at the back of the stage, executing intricate hand and arm gestures as they create a production line of munitions. Smoke engulfs them, and shadows of soldiers are cast in the windows behind them.

The standout moment, however, is undoubtedly the final duet, in which a singular couple, stripped back into simple nude costumes, perform to the sound of a grand piano, which creates a more intimate atmosphere than the preceding full orchestra. Their bodies seem inseparable as they orbit and wrap themselves around each other, yet of course they have to part. The male dancer pulls himself away, and the final image of the piece is of him dragging himself over the trench like structure at the back of the stage, as his partner watches helplessly from afar.

Russell Maliphant’s Second Breath is a contrasting work, as Maliphant applies his renowned abstract approach, yet still accesses the raw emotion of the subject of war. The piece, which Maliphant describes as a “lament”, has a very global reach in that it is not set in a certain country or context. Snippets of text spoken in English, Italian and German are interspersed in the dream-like soundscape, that also includes a distorted, haunting refrain from Auld Lang Syne (with different lyrics.)

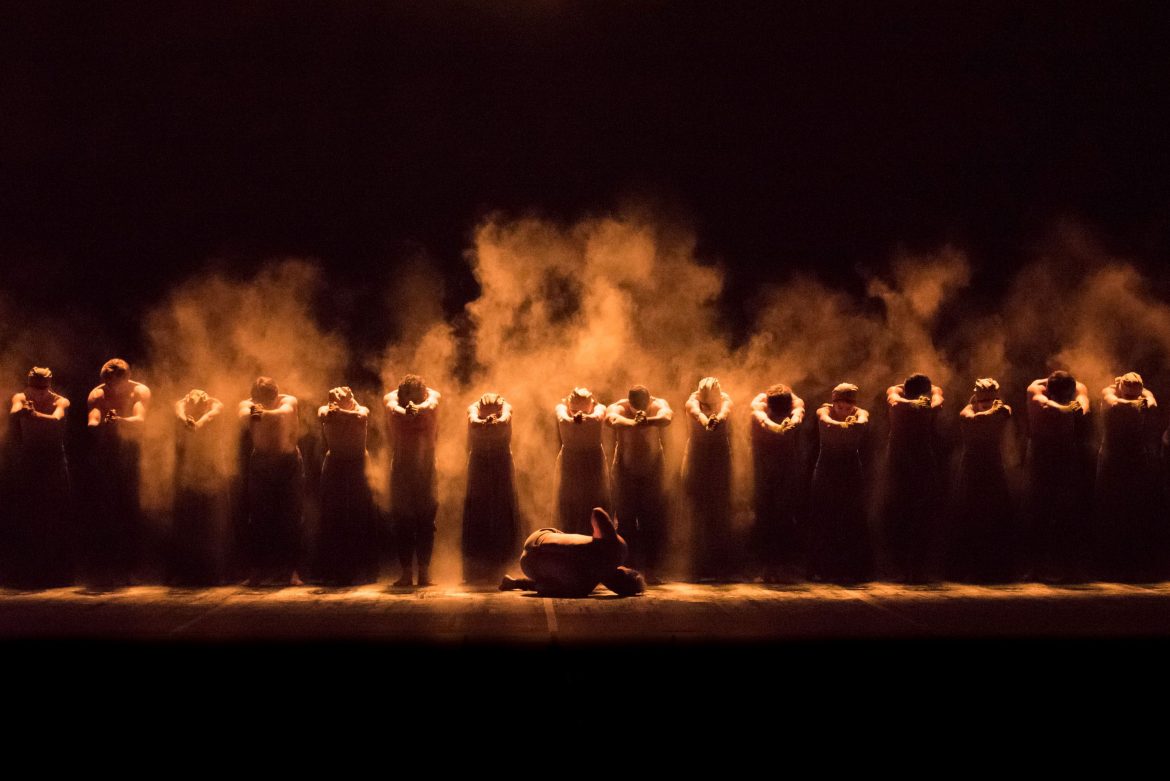

The movement of the large group of dancers constantly flows, as performers are deftly elevated into the air only to sink back down in what appears to be a reference to “the fallen”, a phrase often employed to reference those who have died for their country. Unlike Scarlett’s piece, the cast of Second Breath are completely integrated, their non-representational costumes neutralising them, and metamorphosing their bodies into the vehicles for creating visual metaphors, opposed to being human characters telling their individual stories.

Last but not least is Akram Khan’s Dust, his debut work as a ballet choreographer that gave him the confidence to create his full-length version of Giselle on English National Ballet in 2016. Pointe shoes set aside in favour of bare feet, the piece opens with a singular figure twitching and hitting himself in a dim spotlight, a line of dancers behind him barely visible in the distant darkness. They eventually make their way forward, and clap in unison as they reach the front of the stage, releasing the dust from their hands that gives the work its name.

Like Scarlett, Khan professes his piece explores the women who worked in munitions factories on the home front, and the key moment that reflects this is when the whole casts joins arms to create a spectacular rippling wave that disembodies their limbs so that they become part of one larger conveyer belt, or machine of war. However, this theme is generally less evident throughout the piece, and the choral-like soundscape, along with choreographic language reminiscent of praying gives Dust an almost religious atmosphere.

ENB’s artistic director and former prima of the Royal Ballet, Tamara Rojo, performs for most of the piece in a unified phalanx with the rest of the cast, which is admirably democratic, and in itself mirrors how war was a leveller, bringing men from all parts of society into trenches together to face the unimaginable as equals.

Overall, Lest We Forget is a compelling programme of contrasting works, which showcases English National Ballet’s ability to deliver visually, emotionally, and intellectually arresting dance. It is a shame however, that in a recurring theme, there were no female choreographers on the menu, and that whilst the female experience was considered in the programme, it did not come from a female perspective.

Whilst some may contend that Arstic Director Rojo is championing female voices in the arts, it is disheartening (especially when ENB have themselves proved the standard of female choreographers with their She Said programme back in 2016) that women are deemed unfit to showcase their work alongside their male contemporaries, and instead have to wait their turn for the next conciliatory platform that sets them apart because of their gender.

Reviewed on 20th of September at Sadler’s Wells