As Wayne McGregor, the director and choreographer of ENO’s new production of Gluck’s opera Orpheus and Eurydice, comments in the programme’s featured interview, ‘opera is the most collaborative artwork you can make’. Originally composed in 1762, and here given in its 1859 re-arrangement by Berlioz with a new English translation of the libretto by Christopher Cowell, Gluck’s work was from its conception, particularly concerned to give a structural role to dance alongside the music. Orpheus’ descent to the underworld is thus framed first by the Dance of the Furies whom he must placate, and then, by the Dance of the Blessed Spirits, following which Orpheus is taken to Eurydice.

And that, in essence, is the story: first Furies, then Blessed Spirits. In a deep, structural sense, the story is about the movements of bodies: first the dead body of Eurydice, which floats in Act 1 at the back of the stage, then the obstacles created by the bodies of the Furies in Act 2 and the fluid permeation allowed by the dance of the Blessed Spirits in Act 3. There is also the fatal turning of the head when Orpheus looks back at Eurydice, and at the very same moment Eurydice’s collapse and second death.

Orpheus’ song was never enough: not for Eurydice who needed to look into her lover’s face, and not for Orpheus himself, who was unable to reassure her with his music alone. The myth of Orpheus is thus as much that of the divine musician as that of the tribulations of the body.

In Gluck’s version, however, there is a happy ending, since it will be Orpheus’ post-second death aria of despair – one of the most famous arias of the opera known in its original Italian as ‘Che faro’ senza Euridice?’ and which in Cowell’s brilliant and discreet translation is now ‘Where is love without you near me?’ – which earns him the pity of Amore (Love) who will restore Eurydice to him.

This restoration gives us, in McGregor’s production, a shadow dance in which Orpheus’ dancer-soul, (danced by the bold and beautiful Jacob O’Connell), twists and twirls around Eurydice, sung by Sarah Tynan with just the right vulnerability and certitude gained through love; whilst at the same time, Eurydice’s own dancer-soul, danced by the sculptural and Grecian-paced Rebecca Bassett-Graham, supports and envelops Orpheus.

The effect is that this resuscitation does not in fact bring together the two protagonists, since each is dancing with someone else – someone else who happens to be the shadow-dancing-soul of the other. Separation and eternal togetherness are thus made concrete in one and the same moment. The song says one thing, the dance reveals another.

It is one of McGregor’s achievements to maintain the ambiguity of the narrative – between reality and dreams, life and death, love and loss – in such a way that the unlikelihood of the happy ending is lifted through the suspension of compatibility between song and dance.

This is, in fact, a deep philosophical insight into the nature of dance: it reveals truths which words and even music can so expressively deny. Dance is however so subtle and its touch so soft – it is the cradle of compassion – that it lets everyone pretend it is not in fact showing the opposite of what is being said and sung.

Can Eurydice really come back to life? Perhaps… the time of a dance.

One of the enduring charms of the opera is the sweetness and mellowness of its music. It is not bombastic, has no extreme highs which cover up less exciting lows as so often in operas. The music is consistently suave and enchanting. That velvety quality of the music is exacerbated in this production through the creation of atmospheres of interiority, which are particularly conducive to nourishing the ambiguities the work is constructed on.

The collaboration McGregor so relishes has created a subdued intimacy in which it ceases to be clear, to Orpheus or to the audience, who is absent from whom and who is dead to whom. A desertic stage, shades of dark blue lighting and the presence across the length of the stage of a video screen which serves as a skyline in which the black and white pixels of image fuzziness set the mood like a grey river of Lethe (of death and oblivion) running above the characters’ heads rather than below their feet.

This digital presence, common in McGregor’s work (see 2012’s Infra, or 2015’s Woolf Works), exacerbates the effect of estrangement, by foreshortening the dimensions of the stage. This is particularly striking during the central scene of Eurydice’s second death in which Eurydice’s pleading gnaws, step by step, at Orpheus’ resolve not to turn back and look at her. With every stage of the fatal dialogue, the screen above their heads displays changing geometrical figures like a moving Mondrian painting, in which each rectangle represents a further degree of intensity and doom. Geometry takes on the role of the musical beat, the slow controlled movements of Orpheus – who must not turn around – track Eurydice’s heartbeat; when Orpheus does finally turn his head, the heartbeat stops and dies with the movement.

Everything in the staging is trembling just under the surface with compunction, delicacy. A lot of the high-speed sharpness and charged storminess so characteristic of McGregor’s choreographies has been subdued into a vocabulary which is more idyllic and less corybantic as though the magic of Orpheus’ musical gift has cast an enchantment on the dancers.

The group pieces of the Furies and the Blessed Spirits are especially striking for the costumes designed by Louise Gray, which become fluorescent in the dark blue light. The Furies do a lot of big springy side jumps and the Blessed Spirits have heart-shapes on their bottoms which contributes to bring together different worlds: harlequinesque, care-bears, but also tribal costumes from a future which might or might not be everlasting death, and the dancers, angels or demons.

The counter-alto pitch Orpheus’ role is set at means that it is often a woman who sings the role – it was so when Berlioz first re-arranged the opera in 1859 (replacing the castrato voice the role was originally written for). In our times, women often sing these roles, but there are also exquisite counter-tenors around, which makes the competition between singers of the lower womanly pitch and the higher manly tone very tight. Both have to be earth-shatteringly remarkable to produce an earth-shattering effect which is – because in part of the digital technology McGregor has such profuse recourse to – what we, spoilt 21st century audiences, expect. Here we have Alice Coote, a wonderful singer, and an experienced interpreter of male roles in opera, whose voice is a mellifluous homogenous purr. And yet, she’s not the Orpheus this high-tech production needed. Something more on the edge was required to make this Orpheus perfect.

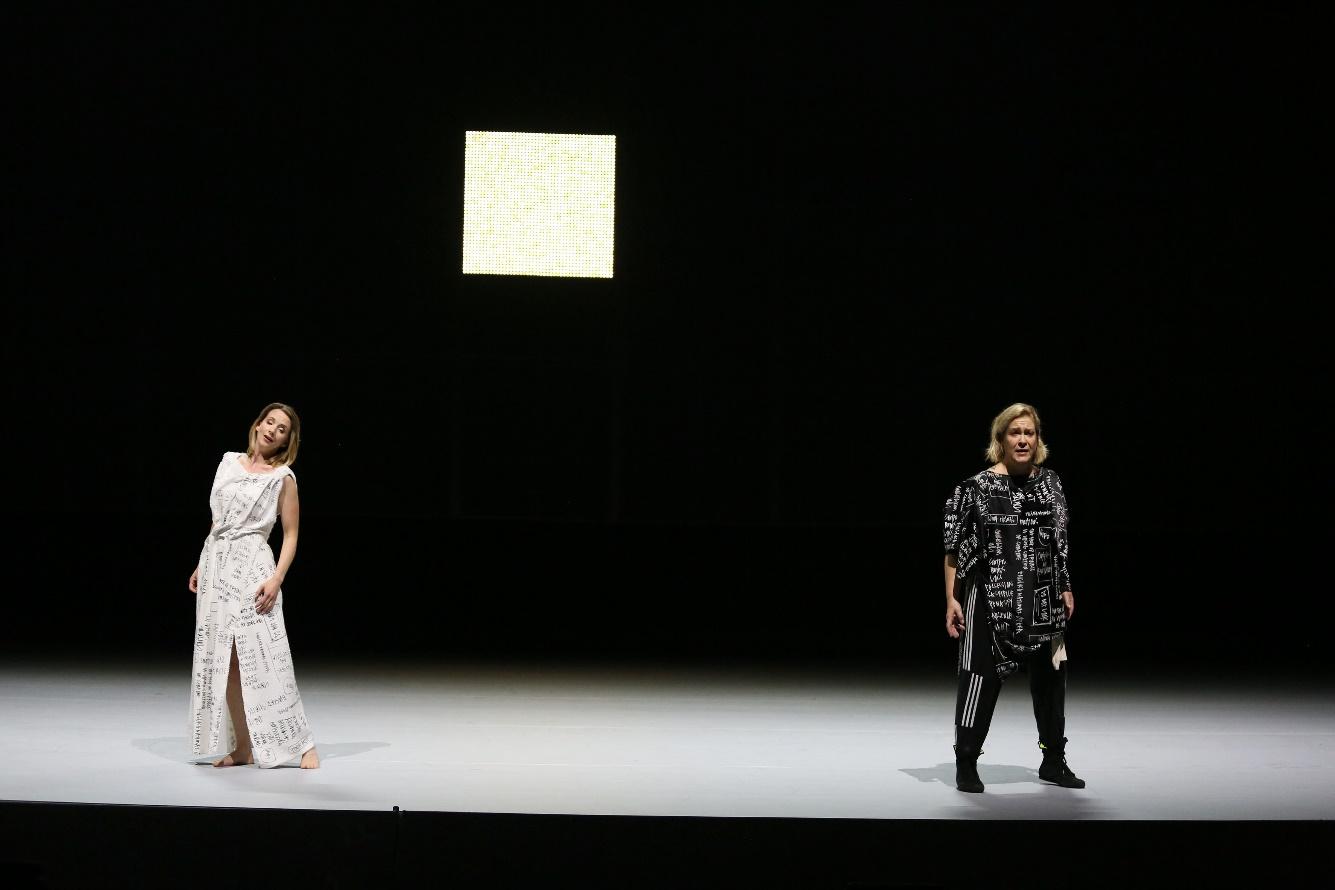

McGregor has dressed Coote… in himself: his characteristic black and white designer sport-chic comfortable but weird attire gives Coote/Orpheus a springy futuristic look in ankle-high black trainers which, together with her bedraggled hair and fluorescent orange eye-liner, gender-neutralises the character.

But the ambiguity is there, and of course, is precious to the general blurring of all lines and dimensions. The two women display moments of heightened physicality in the relationship with embraces and a constant to-ing and fro-ing like magnets which not even death can pull apart. McGregor as director manifests an acute sense of the position and relation of a body on stage. Though the singers do not, officially dance, their movements are choreographed and ordered to infuse the visual effect at every moment with the depth of meaning.

The woman on woman duo is re-enacted by a heart-wrenching man on man pas-de-deux danced by Izzac Carroll, a new face and body from Studio Wayne McGregor Company, whose graceful arms do not seem to end and the wonderful Jordan James Bridge, who seems animated by a perpetual flow of energy. This pas-de-deux is sensational in its naturalism and tenderness, no bubbling violence and feats of strength, but only roundness, continuity, love.

In this doubling up of the musical duet sung by Coote and Tynan with the physical parade of two male dancers, there is something sweet and humorous as if to say that no one is pretending our Orpheus here is a man, and to acknowledge the sapphic pair, here is their homoerotic counter-parts. But of course, there is something more to it: the explosion of the gender game in which there is man in the woman, and woman in the man.

Beyond these questions, McGregor is also making a strong claim for dance’s capacity to say what is really in our hearts; that love is a relation between two bodies which neither words, nor even song, can say as truly as can dance.

Reviewed on 12th of October in London Coliseum